The morning chorus of songbirds has quieted. The spring sunshine has dried the dew and warmed the rocks. Sprinkles of mica glint in the thin soil under your feet. Green darners hunt over the beaverpond, while a swallowtail settles on to a bed of moss and lichen behind you. Rufous-sided towhees sing from scattered pines, common yellowthroats and swamp sparrows flit through the willows along the shore, and a hummingbird buzzes by you on its way to a patch of columbine. As you sit peacefully on 800 million year-old gneiss eating your sandwich, you watch a Blanding’s turtle crawl out warily on a beaver lodge to bask. You have just fallen in love with the Carp Hills.

The Carp Hills rise as a rocky ridge between the valleys of the Carp River and Constance Creek. A mosaic of rock barrens, rocky, open woodlands, and dense mixed forest, I find them most inviting in mid-May, ahead of the swarms of blackflies, mosquitoes and deer flies that torture the summer visitor. I like to arrive just before dawn, when the dew is still heavy enough to soak the hem of my pants. Venus may still glitter over the turquoise horizon. Birds begin to sing from every tree and shrub. A beaver creases the mirrored surface of its pond, on the way back from its last foray of the night. As the morning warms, the dragonflies and butterflies begin to stir. Turtles and snakes come out to warm themselves in the sun. Dewdrops cling like diamonds to cobwebs and spring flowers. Before I realize it, I’ve spent two hours in wonder and barely moved 200 meters from the road.

The Carp Hills, along with the nearby South March Highlands, consist of Precambrian bedrock — an island of ancient metamorphic rock in the sea of younger, Paleozoic limestone that underlies most of Ottawa. The large mineral crystals exposed in the rocky barrens attest to their formation and slow cooling almost a billion years ago, deep under a towering mountain chain created by the collision of continents. Time and the inexorable force of water eroded the mountains, exposing their roots.

When subsequent upheavals in the earth’s crust created the great geological rift that we now call the Ottawa Valley, the Carp Hills remained elevated above the surrounding landscape. Oceans came and went, laying down beds of limestone across the region. More recently, Ice Age glaciers further scraped down the bedrock. When the last glaciers receded 14,000 years ago, a shallow cold, silty sea followed behind them, depositing thick layers of clay over much of valley. As the land rebounded from the weight of the glacial ice and the sea receded, massive rivers of glacial meltwater carved channels and dumped loads of sands and gravels. Through it all, the Carp Hills remained islands of stone, facing and mirroring the Gatineau Hills to the east.

Despite their cataclysmic history, or perhaps because of it, the Carp Hills exhibit an exquisite sensitivity to disturbance. The Precambrian rock provides few nutrients for plant growth, and much of it is sensitive to acid rain. The thin soils have formed almost solely through weathering of the bedrock, the action of microbes, lichens and fungi, the sprinkling of atmospheric dust, and the painstaking accumulation of organic matter. The wetlands, beaverponds and creeks that pocket the hills have adapted to the lack of nutrients, providing habitat for organisms that might not survive competition in more fertile environments. Every living thing in the Carp Hills exists in a delicate and easily upset balance.

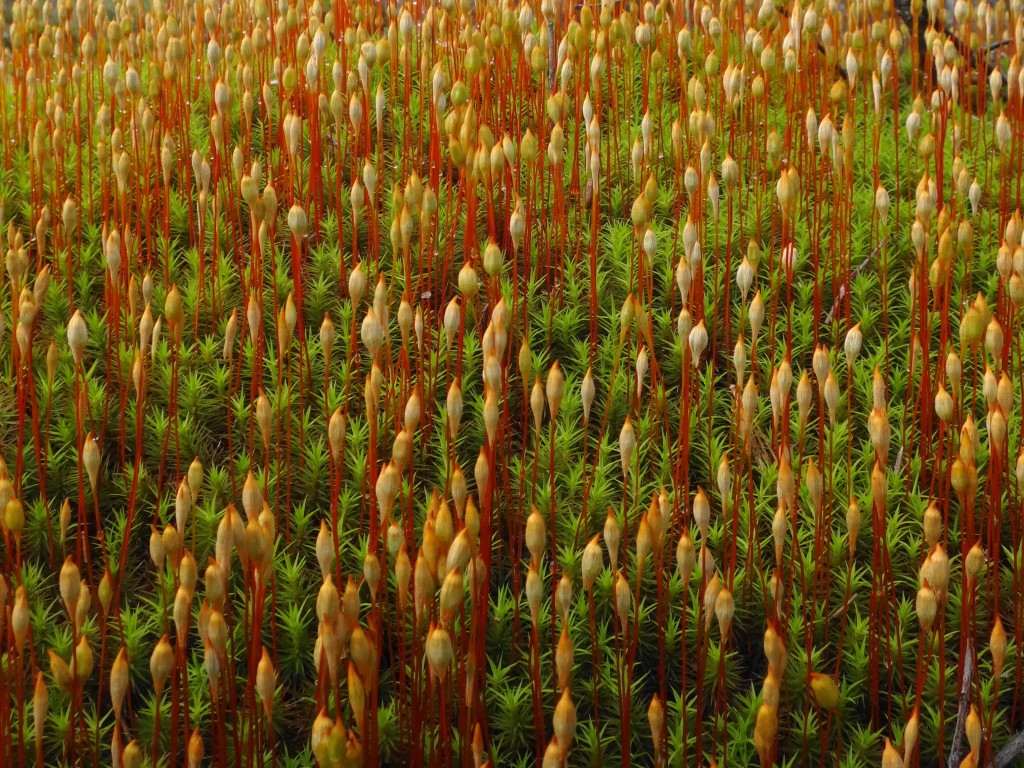

The Hills call for a gentle presence. Even the old Sierra Club motto — “take nothing but a photograph, leave nothing but a footprint” — does not suffice, particularly in the rock barrens. A careless footstep on a delicate moss mat may undo 10,000 years of soil formation. The track of a single mountain bike remains visible for weeks, while regular bike traffic leaves a coarse scar. In such an exposed landscape, plants and animals rely upon every stone and every patch of vegetation for protection. Snakes hide and hunt in the moss carpet. Bats shelter from the sun under stones. Many species at risk make their homes here. Disturbance should be minimized. Whenever possible, visitors should keep to the bare rock to protect the soil. Stones should be left where they lie, and if turned over to look for wildlife, carefully replaced.

Even with such precautions, visitors will find more than enough to admire, photograph, or paint. Wildlife and landscapes abound. But, I particularly like to “get small” in the Carp Hills, to discover the world hidden at my feet.

The City of Ottawa owns significant portions of the Carp Hills, but much of it remains privately owned. With City permission, the Friends of the Huntley Highlands (http://huntleyhighlands.com/) have created the Crazy Horse Trail off March Road, at the east end of the Carp Hills. This low-impact walking and ski trail encompasses almost every habitat in the Hills, including forest, wetland and rock barrens. A more informal, unmarked trail exists on City property off Thomas Dolan Parkway, in the heart of the rock barrens. Parking is limited to the shoulder of the road, which can be very narrow, steep and soft in places.

As an old mountain biker — one who pre-dates the actual creation of the mountain bike — I understand the urge to ride the rock barrens of the Carp Hills. But I ask mountain bikers to respect and protect the delicate nature of the landscape. Even the most careful rider cannot help but cause long-term damage to the ecosystem. Consider, instead, the nearby South March Highlands Conservation Forest, where the Ottawa Mountain Bike Association (http://ottawamba.org/cms/) maintains an outstanding trail system, with a range of technical difficulty to challenge the most avid rider.

The Carp Hills are predominantly wild. A few black bears roam the area, especially in mid- to late summer when berries are ripe in the barrens. In late autumn, deer hunting occurs in some areas. From mid-May until early September, blackflies, mosquitoes and deer flies occur in abundance. Deer ticks, which can transmit Lyme Disease, may abound in some years. There are no facilities and no safe drinking water (due to the presence of beavers). In short, visitors to the Carp Hills should bring water, snacks and other essentials, consider insect repellent, wear long pants and sleeves, and be prepared to adapt as necessary.

Despite these few inconveniences, the Carp Hills are worth the effort. They are a marvel of biodiversity, a window into the distant past, a living classroom, an artist’s inspiration. They will remain in your eye and your mind long after you leave them, and you will return to them year after year.