We glide on dirty, brown water under a green, sunlit canopy of silver maple trees. Spring run-off on the Ottawa River has pushed nutrient-rich floodwaters back into the forests along lower Constance Creek. Warblers sing brightly in the tree-tops and multi-hued wood ducks peek shyly from the shady depths of the swamp. The nighttime chorus of spring peepers and tree frogs has dwindled in the warming day to a few desultory chirps and clucks. We pass between the spreading, fluted tree trunks in quiet awe, like visitors to some southern, bald cypress bayou. But instead of alligators basking along the channel, map turtles and painted turtles crawl on to logs to sun themselves, while pike and gar lie up in the shallow reed beds.

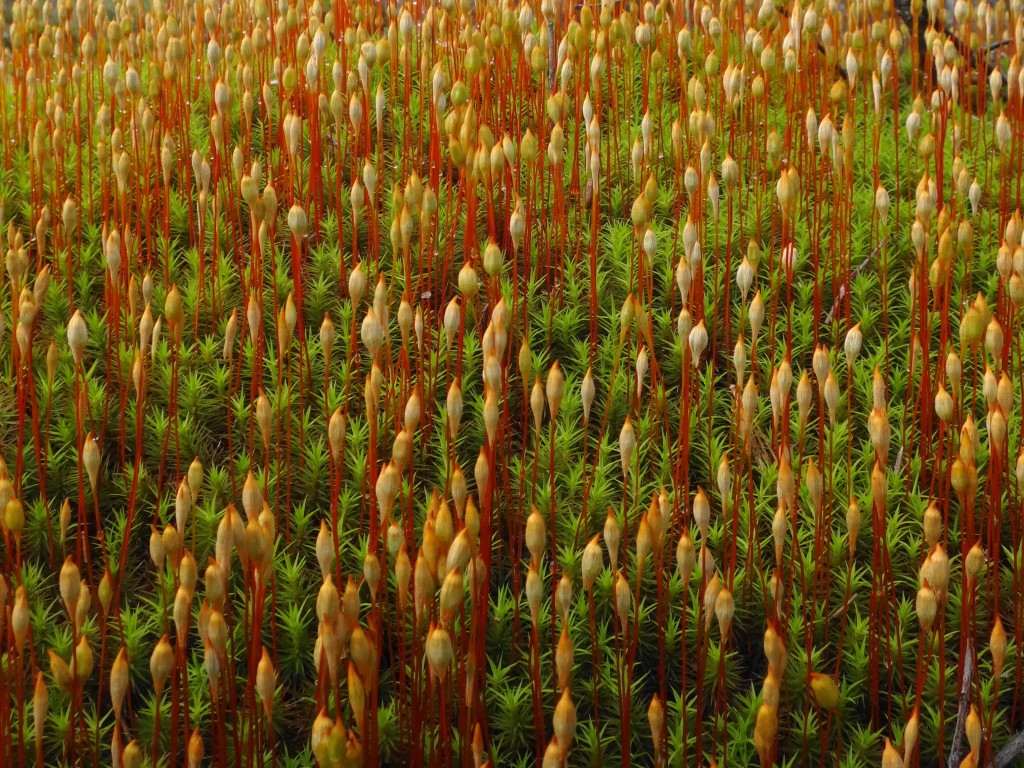

When biologists speak of the diversity and productivity of wetlands, they have places like Constance Creek in mind, where life overspills its banks. Scoop the creek water into your cupped hands, and you hold a galaxy of microscopic, living things. Look up to the trees to see life thrust by the laws of thermodynamics toward its origin in the dust and energy of stars. Energy flows through a tangled web of matter, seeking stability, building in complexity, expressed in a fractal lattice in which dragonflies hang like jewels. A wetland brings together the elements of life like no other place. Perhaps in no other place does a biologist feel more like a priest.

A confluence of fortuitous circumstances has preserved Constance Creek as a uniquely healthy riverine wetland. About 10,000 years ago, when meltwaters of the retreating glaciers swelled the Ottawa River, part of it flowed along a side channel from Constance Bay in the north to Shirley’s Bay in the south. Along the banks of this channel, it deposited large sandbars over the flat clays left by the retreating Champlain Sea. Over time, as the Ottawa River shrank to its current size, flows along the channel reversed direction, draining the adjacent Carp Ridge and Dunrobin Ridge north through a meadering stream and wide, swampy floodplain. Annual flooding limited farming and permanent settlement along the creek, while the deep, sandy soils supported the growth of a rich riparian forest to further screen and protect the creek. Some unauthorized filling of the Constance Creek wetland occurred in 1989 with the construction of the Eagle Creek Golf Club. Sand pits have also opened at places along the creek, although they remain hidden from the main channel. For the most part, though, the creek remains well buffered from surrounding land uses.

Several locations give access to the creek, but thick cattails often limit paddling. At the upper end, an alm0st impenetrable marsh blocks access from Constance Lake. The reach downstream of the bridge at Thomas Dolan Parkway provides a short, easy paddle through a lovely riverine marsh. Painted turtles, snapping turtles and Blanding’s turtles bask along the channel in the midday sun, and a colony of black-crowned night herons hides back in the reeds. Damselflies and dragonflies hunt over the water. The bridge at Vance’s Side Road provides a pretty view over marsh and swamp, but the channel quickly chokes off both upstream and downstream. In contrast, the mouth of the creek on Constance Bay offers one of the most beautiful, flat water paddles in Ottawa.

I like to start my trips up Constance Creek at the far, north end of Greenland Road, where the City-owned road allowance runs up to the water at tiny Horseshoe Bay. I paddle through the sandy shallows, tracked by freshwater clams and mussels, into the wider expanse of Constance Bay. I don’t recommend it for breezy days, when the wind driving across the wide river can raise substantial waves. But on calm days, the glassy water parts smoothy to either side of the bow, as I round the point to the west. Sometimes I paddle straight across Constance Bay to the mouth of the creek. More often, though, I skirt the shoreline, looking for turtles and scanning the flats for longnose gar finning in the shallow water.

Constance Bay provides some of the best fishing along the Ottawa River shoreline. The clean, Ottawa River, the shallow reed and weed beds, and the steady influx of nutrients from Constance Creek create a perfect mix of spawning, nursery and adult habitats. Although I haven’t yet tried flyfishing for longnose gar, I’ve heard that they rival bonefish for fun. The technique seems roughly the same, and one can find lots of instruction online. Usually, however, I troll a streamer fly or a spinnerbait behind the canoe and pick up some of the pike for which Constance Bay is famous. Musky also lurk in the weeds, although for the sake of my light tackle (and their health), I don’t try for them. Closer to the mouth of the creek, though, I’ve caught catfish and bass. Walleye forage in deeper water, along the outer edge of the bay. At times, in fact, fish have struck so frequently as I’ve paddled across the bay, that I’ve had to bring in my line to make any real progress toward the creek.

Constance Creek flows through a stunning swamp forest into Constance Bay. Large, mature silver maples line the banks along the channel, while swamp bur oaks sit further back on slightly higher ground. During the spring flood, one can sometimes paddle into the swamp itself, threading between standing and fallen trees. Great blue herons stalk along the boundary of swamp and stream, while pileated woodpeckers cackle and hammer deeper in the recesses of the forest. In the autumn, ducks and geese descend like leaves into the marshes around the creek mouth, and the sounds of shotguns echo distantly from further up the creek, where several duck clubs operate hunting blinds.

Not surprisingly, many of Ottawa’s most interesting animals and species at risk find a home along Constance Creek. Five of Ottawa’s six at-risk turtle species have been recorded along the creek and at its mouth, including the extremely elusive (and possibly extirpated locally) spiny soft-shelled turtle. Red-headed woodpeckers still nest locally. Terns no longer nest in the area, but pass through during migration. Ospreys can often be found hunting along the creek. Bald eagles migrate along the creek and the Ottawa River shoreline, as do many other raptors, including peregrine falcons. Lake sturgeons and American eels still inhabit the waters.

This richness of life is no doubt what attracted aboriginal peoples to the creek. Archaeologists have documented at least one 2500 year-old camp and burial site at the mouth of Constance Creek, on its west shore (https://ottawarewind.com/2014/02/24/ancient-ottawa-lost-relics-from-500bc-found-at-constance-bay/). More undocumented sites seem likely, perhaps in the large woodland on the east side of the creek mouth. Unfortunately, that woodland remains at risk of future aggregate extraction. Lying atop one of the largest, untouched sand and gravel deposits in the north end of the City, it currently enjoys protection by Provincial wetland policies and an unopened City road allowance. These prevent the legal access required for an aggregate license. Nonetheless, so long as the property remains privately-owned, the threat exists.

In the meantime, one can travel back 2500 years with just a canoe trip up the creek. The present swirls behind from the blade of your paddle. Lying quietly up in the swamp, daydreaming and staring serenely up at the translucent leaves, one can easily imagine that it has always appeared this way. With a whisper of wings and ragged croak, Raven passes over the canopy. Floating there, you surrender to thought and memory.