I fell in love in Algonquin Park. We arrived with our sons at the Brent Campground late on a dark night, desperate for our sleeping bags. Leaving her tent in the car for the night, I assembled my larger tent and then the four of us bundled into the cramped, humid space. I slept fitfully and woke early, as the pale light seeped under the fly and through the nylon. She lay facing me and I thought, “wouldn’t it be lovely to wake up to this face for the rest of my life?” Later that warm, summer day, she turned cartwheels on the beach. On the drive back to Ottawa, she put her bare feet on the dashboard and sang to the radio.

Memories of Algonquin Park go back generations: a dozen or so for settlers; 500 or more for Indigenous peoples. A canoe glides over still water at dusk, while a loon calls across the lake, and a moose grazes in the shallows. The face in the canoe changes over the centuries — Anishnabe, explorer, trapper, logger, camper, tourist — but the experience and wonder remain constant. They imprint themselves on the individual and collective consciousness.

Of course, so do the blackflies.

I try to time my visits to Algonquin Park for early May, before the blackfiles and mosquitoes emerge, or for September after the first cold nights. Not June. Never June. Except this year. This year, the Fates seemed determined to thwart my plans: critical meetings, slipping deadlines, family obligations. I postponed my trip once, then again. Early May slid by, then mid-May, then late May. Not until the first week of June did I find myself pulling into the Mew Lake Campground.

All that week, I crept early into my tent at night and rose at dawn. For the first time in years, I didn’t light a fire. When the sun came out, so did swarms of blackflies. At night, or under the deep forest canopy, clouds of mosquitoes rose from the underbrush. More than once, I retreated to the Lake of Two Rivers Cafe for lunch 0r supper for an hour’s respite.

Not once, though, did I regret the trip. Morning mist rising from a lake or beading on a canvas of spiderwebs. Pink ladyslippers blooming beside a trail. A lichen-encrusted boulder reflected in a stream. The rolling hills and forests spread below a fractured cliff. The flush of new needles on a tamarack — “a little green”, as Joni Mitchell describes it. The slap of a beaver’s tail somewhere out on dark water. Moments of wonder and beauty capture in images and memories.

Of course, memories needn’t always come with the scent of DEET. Autumn may be the finest time to visit Algonquin Park, cool fire-lit nights and warm, bug-free days. Early in the season, the lakes may still be warm enough to swim. Colourful, quilted hills rise from shorelines. Life at its most abundant, before the long migrations south and the long hibernation. By the end of fishing season, the brook trout and lake trout have begun to emerge from the summer depths to chase a spoon or fly. Amorous moose call from clearings and wetland meadows. In the evenings, loons lament the shortening days.

I recall rising from my tent one morning before sunrise to look out over the Barron River. Standing on the shoreline in the quiet darkness, I puzzled at the sound of crunching coming from both up and down the shoreline, as well as on the far shore. Only later, in the growing light, could I make out the shapes of beavers in the shallows munching water lily roots like candy. Later that same morning, as my son and I cooked breakfast at the fire, the alarmed chatter of a red squirrel alerted us to a pine marten peering around the thick trunk of a white pine. In the afternoon, we pulled fat bass out of the river.

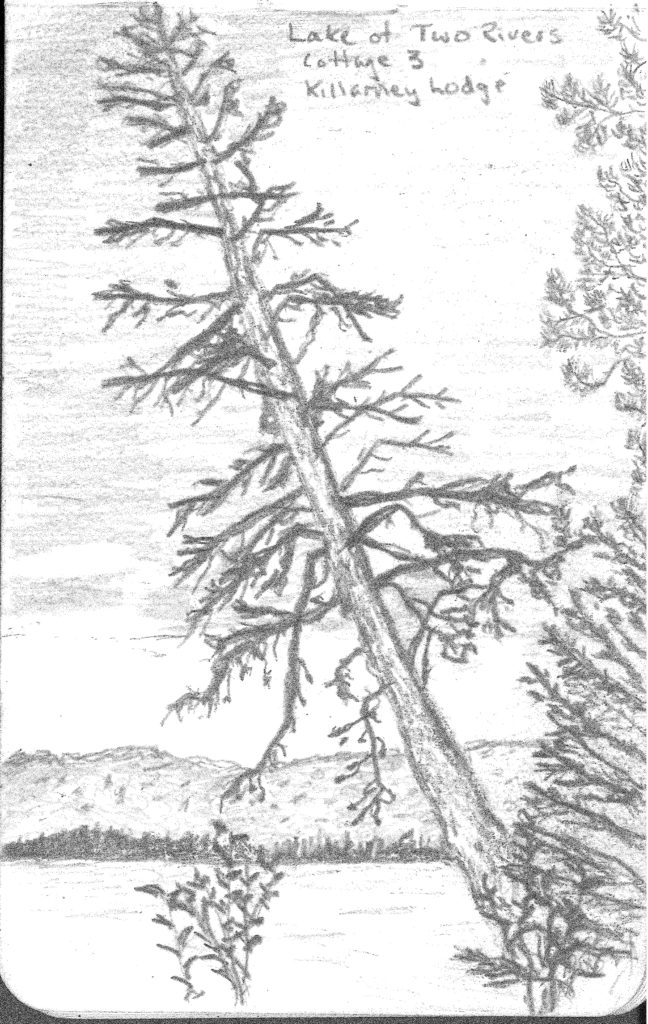

On another, autumn weekend, my wife and I rented a shoreline cottage at Killarney Lodge. Sitting on the deck in the sun, we read books, sketched, fed peanuts to the resident chipmunk, and looked forward to the next gourmet meal. We rented bikes at the Lake of Two Rivers and cycled along the old rail line under gold and red trees. We slept with the windows open, snuggled warmly under our thick blankets, welcoming the scent of the pines and the sound of wind in their branches.

I have yet to visit Algonquin Park in winter, but would love to see it on one of those bright, cold January days, when the snow is dry and powdery, the spruce trees crack and creak, and the whiskey jacks complain at your passing. I would like to see the steam rising from a beaver lodge, surrounded by the exploratory tracks of a wolf. I would love to hear Raven croak a greeting and hear the rustle of his wings as he flies overhead. I would love to follow an otter slide from lake to lake. I would love to return to a warm fire and steaming cup of hot chocolate at night.

Some things, like hot chocolate, should be shared. As much as I enjoy a solitary trip in Algonquin’s back country — quietly walking the trails, listening to the sounds of night, and rising silently in my own time — I almost prefer the shared experience. Since the last ice age, 10,000 years ago, humans have travelled the waterways and ridges. Where settlers now camp, Indigenous peoples once camped. In the dense darkness of cedars, overgrown vision pits speak of ancient spiritual quests. Decayed cabins and log slides lie mouldering beside waterfalls. Logging trucks still rattle and bang along dirt roads, where trees fall to chainsaws. Paddlers eat lunch on billion year-old Canadian Shield rock. Travellers from around the world look out over the Sunday Creek Bog from the Visitors Centre, hoping (not without reason) to see a moose or a wolf. People have always been here, and they will continue to be here. The challenge is to ensure that Algonquin Park remains both a place to find Nature and to fall in love.