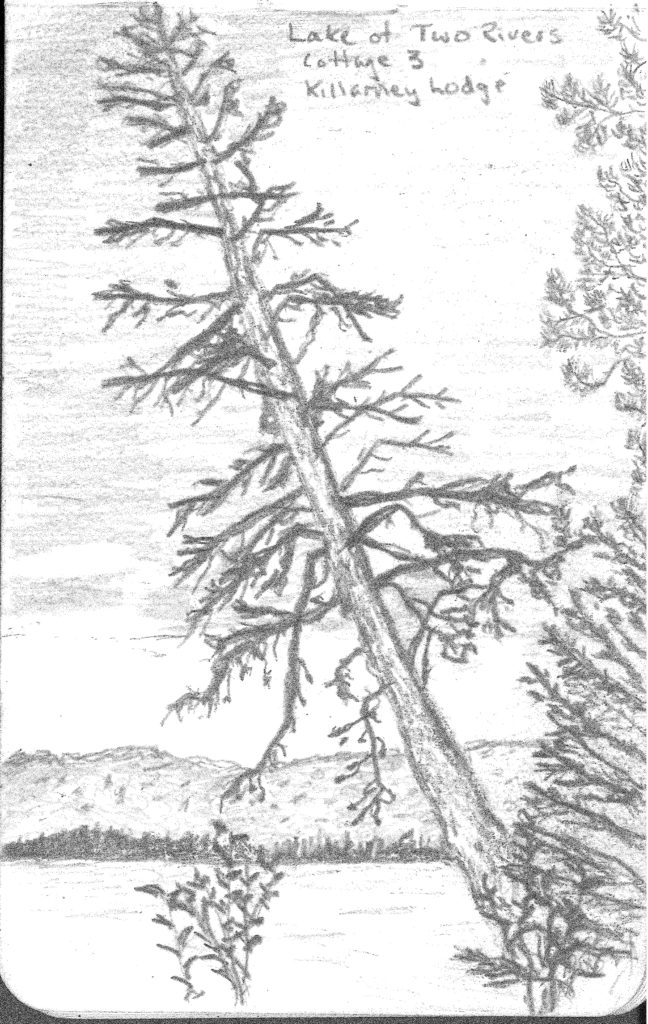

Francis/King Regional Park lies on the outskirts of Victoria, British Columbia. On Saturdays, as a boy, I would often pack a lunch and ride my bike out past the suburbs and fields. I would labour up the long curved hill to the parking lot, and then spend the day exploring the trails. Just inside the edge of the forest beyond the main trailhead, a large, fallen tree lay rotting on the woodland floor. Moss and lichens, ferns, wildflowers, and seedlings of every sort rooted themselves in the damp, pulpy wood. A nearby sign read, “Nurse Log”. A profusion of other saplings and young trees grew in the sunny gap where the old matriarch had laid down her life.

Do not mourn the passing of a forest tree.

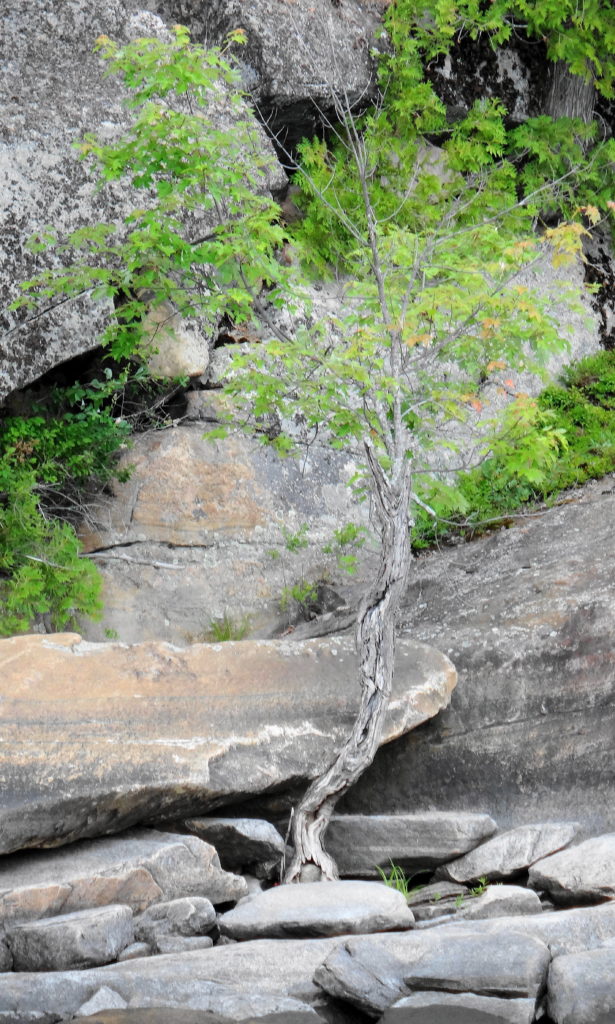

Forests recycle nutrients very efficiently. Long before a tree ever falls in a forest, other organisms have already begun to consume it: ants and beetles burrowing into the wood; fungi spreading their hyphae through the living and dead tissue. Down on the forest floor, the decomposition accelerates. More fungi and bacteria reach up from the soil to colonize the fallen log, secreting enzymes to digest the wood. Microscopic nematodes follow, grazing on the bacteria, fungi, and each other, while likewise providing prey for insects. Snakes, salamanders and small mammals hide and hunt through the decaying log. Mosses, lichens and herbs take root, escaping the thick leaf litter on the forest floor. Seedlings and saplings nestle in the damp, decaying wood. All the while, the old tree slowly sinks and spreads, returning to the earth from which it sprung a lifetime earlier.

The death of a forest tree not only supports new life, but it opens space for that life to grow. Sugar maple, that beautiful queen of Canada’s eastern deciduous forest, casts a deep shadow over her subjects. Left undisturbed in the canopy, she monopolizes the sunlight. In her deep shade, her offspring blanket the forest floor. Only a few equally shade-tolerant trees possess the patience to wait her out: trees such as the graceful beech — slender branches questing outward for wayward flecks of light — and the amicable basswood, sprouting oversized leaves to capture the pale, green glow from above. Only her death frees them to reach for the sun.

In the language of forest ecology, the death of a canopy tree by cutting or natural causes initiates a process of single tree replacement. More often than not, in eastern and northern hardwood forests, sugar maple wins the race to fill the small gap. A cohort of seedlings springs upward into the space. Soon a few dominant saplings subdue the rest and fight for light, until only one remains. The gap provides insufficient light for less shade-tolerant species to overcome the advantage of sugar maple. Consequently, over time, single tree replacement tends to reduce the diversity of the forest canopy.

Only a large disturbance opens the canopy sufficiently to break the dominance of sugar maple. Sometimes the collapse of a particularly large tree brings down several other trees, opening a moderate gap that favours semi-shade tolerant trees like red oak, yellow birch or white pine. Periodically, a thunderstorm will unleash a local, violent microburst, breaking or flattening dozens of trees. In such a large gap, species like large-tooth aspen, white ash, and black cherry may find a favourable niche. In rare instances, a larger event — a tornado or a hurricane — will flatten many hectares of forest, creating a clearing in which early-successional species like trembling aspen and white birch may spawn solid thickets and stands.

In time, the canopy will close and again cast the forest floor into shade. Maple seedlings will carpet the ground, ready to fill the gaps left by other trees. The forest will slowly return to its pre-disturbance state. Forest ecologists call this pattern of equilibrium, disturbance, and succession “gap dynamics.” Across the vastness of eastern North America’s deciduous forests, it maintains their marvelous diversity. It maintains a patchwork of habitats, large and small, for wildlife. It promotes the long-term stability and sustainability of the natural landscape.

Of course, we might find such a detached, scientific view hard to maintain when faced with the devastation of our favourite, local patch of forest. We think of our favourite woodlands as static. Someone might follow their favourite trail between the same towering pines for a lifetime, never perceiving their slow, incremental growth or decline. The loss of favourite tree or grove can strike like the loss of a dear friend. We grieve for them and for ourselves.

Hopefully we can find comfort in the knowledge that in a forest, every death brings new life. Perhaps we can find perspective and solace in the irrepressible force of life that continues regardless of loss, of change, of time? I doubt that any trace remains of the old log that lay in forest of my youth. But I know that its legacy continues.